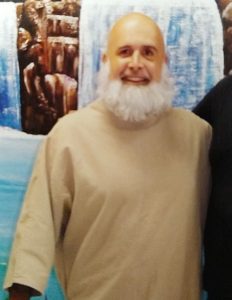

Sean Swain’s segment on the loss of his father, first broadcast September 13, 2020

Also, formatted as a zine, and the audio can be found here.

One of my earliest memories, I couldn’t have been older than three years old. It was in the kitchen of my parents home in Des Moines, Iowa, and my dad was holding me while my mom was on the phone and I was trying to reach out to grab the ceramic Pillsbury Doughboy cookie jar. I lost my dad on March 24th due to complications after heart surgery. He had been waiting to get scheduled for the surgery since before Thanksgiving, but he wasn’t a priority. He didn’t matter to the people to make life and death decisions.

One of my earliest memories, I couldn’t have been older than three years old. It was in the kitchen of my parents home in Des Moines, Iowa, and my dad was holding me while my mom was on the phone and I was trying to reach out to grab the ceramic Pillsbury Doughboy cookie jar. I lost my dad on March 24th due to complications after heart surgery. He had been waiting to get scheduled for the surgery since before Thanksgiving, but he wasn’t a priority. He didn’t matter to the people to make life and death decisions.

He should have. He was a really extraordinary guy. I know I’m biased because he was my dad, but even so, he was an exceptional human being. He was kind and generous and gentle and he really loved life. He and my mom were together for something like 55 years. This has really devastated her. My dad wanted to be cremated, so my mom has his ashes in an ornate walnut box that he would have liked, as he loves to do woodwork and make chains after he retired.

I’m an only child, so my mom’s alone now and it’s hard on her—because she’s really alone. She’s in her 70s and can’t risk getting Covid 19. She’s constantly injuring herself, doing yard work and other nonsense she has no business doing. She needs to be home. I’ve been meaning to share this for some time to help maybe work through this loss, but it’s hard to reduce the words. There’s the pain of missing him. But there is more.

I think, of all that he went through and the sacrifices that he made for my mom and for me. He worked at Ford for 30 years. He hated it. Factory work. Another of my earliest memories, my mom and I were in the car dropping my dad off at the Ford plant. He had on a denim jacket, one of those old black metal lunchboxes, the kind that was rounded at the top, the whole performance. He was in his 20s, that shaggy hair and beard.

Beyond this loss and grief, I feel a sense of injustice for him. The day he died, the world kept spinning. There was no pause, no moment of reflection, traffic kept moving on the highways, everyone kept shopping. The stock market closed slightly up for the day. Apart from my mom and me and a handful of close friends family. It was as if he had never existed, as if he never happened.

Somewhere at the Ford plant on Romeo Plank Road in Michigan, an assembly line worker stood right where my dad spent decades and that worker perform the same job my dad used to do. He or she is probably never even heard of Paul Swain.

So beyond the grief, it was hard for me to wrestle with the sense that the world moves on like that. In fact, it doesn’t even blink, not just for my dad, but for all of us. It makes it feel sometimes like all the struggle and the sorrow, the misery and even the joy that none of it counts. It’s there a God like ashes and a strong breeze. And then so we.

I share this house because it feels like the world over we’re in an era of loss. With covid-19 raging and the fascist march with knees on our necks, with knees on our necks of guns pressing our backs. It feels like everything is for nothing. It feels like doom and gloom. So maybe that is the point. Maybe these cumulative losses, this intolerable meaninglessness, this sense of the hopeless, it all confronts us and it confronts all of us, and it awaits our collective response.

For me personally, I never met George Floyd. I didn’t know him, but I knew Paul Swain. I remember when he was young and that denim jacket, facing the daily small injustices, the humiliations and the reductions. To the thousands of spectacular and terrible atrocities we witnessed, also accompanied by hundreds of millions of more mundane ones that we all experience.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that as I navigate the loss of my dad, it’s important for me to think about how this collective struggle against the current dystopia is to stop the brutality like we saw on the streets and the Minneapolis for nine minutes. But it’s also to stop the slow roasted brutality to which we are all victims.

I don’t just want to end police or prisons. I want to end factories and sweatshops and wage slavery and nation states and chemical warfare and all the components of this immiserating shit society in which we live and shop and work and die.

I want to struggle and win because all of our lives and all of our deaths should matter. Until we have that kind of a world, we owe it to those we love, and to those we’ve lost, to fight for them and for ourselves.

This is Paul Swain’s son. If you’re listening, you are the resistance.